Uncategorized

In "True West," a glimpse of the myth and brutal reality of wolf reintroduction – The Colorado Sun

The Colorado Sun

Telling stories that matter in a dynamic, evolving state.

Editor’s Picks: Colorado is getting older | Child care crisis | “Big, beautiful bill” & Medicaid

Author’s note: The following passage is about a man who operated a wolf-friendly ranch on the edge of the Yellowstone ecosystem. Roger Lang moved to Montana in the late 1990s after making his money in Silicon Valley and buying the Sun Ranch from actor Steven Segal. He ran cows on his land but was also welcoming to elk, wolves, and grizzlies.

In addition to hosting cows, Lang hosted humans, offering elk hunters guided trips, and built a high-end ecotourism lodge. He worked to “cut deals” with nearby luxury developments such as the Yellowstone Club, an elite compound of zillionaires just eastward over the crest of the Madison Range. He stood ready to “helicopter wealthy people into Sun Ranch for a real ranch experience, or hunting, fishing, glamping, whatever you wanted.” Lang explained, “Sun Ranch was a real cattle ranch. We had anywhere from 2,200 to 3,000 cows, depending on the year, in terms of anticipated dryness or wetness, and grass bank. We did a whole bunch of things from carbon sequestration to native, threatened trout restoration.” Lang started a hatchery for westslope cut-throat, a species displaced or hybridized by non-native rainbows and browns in the Madison River among other waterways. As he told me of his work on the Sun, we sat beneath two-story walls of books, him on the couch, me in my red leather chair, as the four dogs occasionally demanded our attention.

“We wanted a ranch with wolves. It was very avant-garde.” It was more than avant-garde. Not only was it novel, it was difficult. Many factors made running a cattle ranch hard, but Lang wasn’t susceptible to one of the most fervid of western myths about that: the myth of the wicked wolf.

Wolves, extirpated from this region in the early twentieth century, were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park in 1995 and have since fanned out through the ecosystem, dispersing beyond park boundaries. The species has been incredibly successful in its return, but packs need lots of territory and lots of food. When Lang owned the Sun, the Wedge pack moved into the eastern flanks of the Madisons and lived with the cattle for years before they began to kill them. Throughout the Northern Rockies, wolves prey on elk in good times and rabbits and rodents in meager times. A wolf pack can take out a moose or a bison but it’s hard work and costs lots of calories. It’s also perilous for pack members. What isn’t as hazardous to a wolf’s welfare is preying on cattle. At least until the rancher seeks retribution.

UNDERWRITTEN BY

Each week, The Colorado Sun and Colorado Humanities & Center For The Book feature an excerpt from a Colorado book and an interview with the author. Explore the SunLit archives at coloradosun.com/sunlit.

In the Madison Valley, one can look across the landscape and see rangelands, or one can see wilderness. Lang sees both. That is why he loves the place so deeply. Raising cows in the presence of wolves and grizzlies takes patience, grit, commitment, and the ability to recover from financial loss and a broken heart. Though there are nonprofit organizations and government programs ready to reimburse owners for wolf and grizzly kills of livestock, most ranchers don’t want to deal with predators killing their animals, nor with the hassle of filing for reimbursement. Lang accomplished something remarkable, but not without a toll on cows, wolves, and his ranch hands.

Bryce Andrews worked for Lang in 2006. In a memoir published in 2014, Badluck Way, Andrews recalls his year on the Sun, managing both cattle and wolves. The book captures the pain of embracing two seemingly contradictory mindsets: a genuine appreciation for wolves and the understanding that this apex predator is deadly to a domestic animal in one’s care. You can love the wild, Andrews tells us, while feeling anguish at its ferocity.

Go deeper into this story in this episode of The Daily Sun-Up podcast.

Subscribe: Apple | Spotify | RSS

Andrews worked hard, moving cattle, tending fence, all the while watching the Wedge wolf pack run like phantoms through the draws and sinuous edges of Lang’s place. There had been a series of cattle predations, and Andrews’s direct boss, not Lang, pressed him—would he shoot a wolf if he saw one? The Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks issued a permit, giving the ranch permission to kill pack members. It was a very troubling request, killing a wolf, and Andrews himself wondered if he would be capable of it. When he later saw the individual male thought to be responsible for the predations, Andrews shot him twice, killing him. That night, he went back out to find the wolf’s body. Sitting in the beams of his truck’s headlights, he touched the carcass, finding the hole in the wolf’s side where a bullet had ripped its way through silvery fur. The next day, he drove to Jackson, Wyoming, for a two-day bender.

Another incident took place some months later, when Andrews found two heifers attacked by wolves, one mortally wounded, her backside in shreds.

>> READ AN INTERVIEW WITH THE AUTHOR

Where to find it:

SunLit present new excerpts from some of the best Colorado authors that not only spin engaging narratives but also illuminate who we are as a community. Read more.

The ranch had been asked to keep the cows alive until officials could examine them, so Andrews watched the heifer struggle to get back to a barn as blood dripped from her torn hindquarters. Her staggering gait and her evident terror nearly made him vomit, so horrible was it to witness. This was an animal under his care and seeing her in such misery wrecked him. Due to the attacks, more wolves were killed.

A year later, after Andrews had left, the ranch was cited for a violation of Montana law when Justin Dixon, another hand, driving a four-wheeler, chased the pack’s alpha female suspected of attacking livestock. Lang told me that Dixon had shot the wolf a couple of weeks before the incident without telling him, injuring the female and making it more difficult to hunt. When Dixon caught up to the female, he ran her over with his all-terrain vehicle, crushing her body under its wheels as she yowled in pain. When Lang got the call about her capture, he also heard ranch dogs snarling and snapping as she lay pinned.

Wedged, still alive, between the dirt and 700 pounds of metal, the wolf struggled while someone went to find a rifle to finish her. It was crushing to Lang, who couldn’t sleep well for three months. A blow to his ranching ideals and a stab in his heart. He later issued a statement saying, “I am very sorry that this event happened on any ranch let alone our own. We condemn all inhumane treatment of animals.”

Lang later told me that, at the time, the population of wolves on his ranch had totaled fifteen and that “anything north of ten created problems.” As in problems when predators tangle with livestock and myths of agrarian cultivation are confronted with the hungry wild.

There is a history of disregard for wolves in the American West. As land was settled in the 1800s, white newcomers wiped out elk and deer populations through overhunting, forcing wolves and other predators to livestock as a source of food. European agriculturalists brought their culture to America, so the lobo was reviled on American soil as immigrants streamed West. These beliefs are still firmly held. Lang’s ranch hand, Justin Dixon, hails from a small Mormon town in northern Utah and grew up in a culture with deeply ingrained biblical notions about nature that Christians carried with them from the old country.

John D. Lee, an early western settler and an infamous figure in Utah Territory, also shared this culture and set of beliefs. He wrote in 1848 about the critters slavering over livestock and wild animals, noting in his journal, “Among the Many, the wasters and destroyers was taken into consideration, to wit, the wolves, wildcats, catamounts, Pole cats, minks, Bear, Panthers, Eagles, Hawks, owls, crows or Ravens & Magpies, which are verry numerous & not only troublesome but destructive.” To rid themselves of these “wasters and destroyers,” Lee and others organized a hunt, beginning on Christmas Day in 1848, to wipe out predators. The campaign was recorded in Latter-day Saint records as “Articles of Agreement for Extermination of Birds and Beasts.”

When tallied in March 1849, the total number of animals exterminated was 2,057, including 331 wolves and 216 foxes.

Yes, wolves can threaten domesticated animals, but their vilification far exceeds their offenses. In European fairy tales, wolves eat grandmothers and menace little girls, while in the Bible, the wolf threatens shepherds and their flocks, serving also as a metaphor for a false prophet. In other words, in Judeo-Christian myth, wolves are dangerous and mendacious. Considering the disregard that Dixon showed towards the female wolf on Lang’s spread, it’s impossible to ignore another biblical myth, dominion, an idea also mentioned by the Bundy family to substantiate their range war. At a rally in 2018, Ammon Bundy, who is LDS, told an audience, “I first need you to know that I’m a Christian.” He then invoked Genesis, while claiming his own dominion in subduing the earth. Earlier that year, his brother Ryan Bundy, dressed in a tight leather vest, spoke to a group in Paradise, Montana, telling the crowd (which included me) that Genesis gave “man” full sovereignty over the land and authority over every “creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.” Man (his word) was given the freedom, Ryan continued, to do whatever he pleased with the animals, plants, landscapes, all placed here for his use, his pleasure, and his disregard.

After one of my several meetings with Roger Lang, I was reminded of Jaren Watson, another member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who grew up in southeastern Idaho, not far from Dixon’s origin. In an essay published in Origami Journal, Watson wrote of his own experience in encountering a fox, another one of those wasters and destroyers, when he was a kid. Like Dixon, Watson pursued the animal on a machine, a snowmobile in his case, with his brother. The boys chased it to the point of exhaustion, then ran the poor creature over. “It merely ran,” Watson wrote. “It ran through belly deep snow with heroic effort. It ran and ran and kept going, churning the snow under foot. Eventually, it tired.” The animal finally became resigned and just stood in the snow, head bent. The boys gunned the engine. “It wasn’t much, running over that small fox. The sensation was like swallowing some too large thing, a momentary catch, a pressing against the soft flesh of the throat…We had broken its bones. Its slender front legs zigzagged at severe angles. Some of its insides were outside. We had smudged it.”

Writing as a grown man, Watson conveys both experience and regret for his needless callousness. He had come to understand the loss of this animal, a small predator making its living in the wild, and his youthful role in its brutal and heartless end. “Of what consequence, this mere fox? Passing over this bit of fur, this bit of bone. Noticed by no one, perhaps, save only him, who notices the fall of every sparrow. Good God in heaven, who among us had not where to lay his head, forgive me. I was a boy then. I was only a boy, and I took unto myself a lump I couldn’t swallow. I cannot swallow still.” Watson asked God to forgive him for the senseless killing—one accomplished because as a human, he had the tools, and God-given dominion, to take its life.

That humans kill things wantonly embodies the myth of a God-given dominion over all. It’s an idea that humans are somehow superior because humans are created in the image of God, while wild nature, wild animals, are inferior, just as a cultivated garden is “superior” to a native grassland or forest.

This myth makes it easy to kill wild things and to hate undomesticated animals. Without reflection like Watson’s, a harmless fox, let alone a fierce wolf, remains for many people something to distain, to torture, and to kill.

Actions like running over a wolf or a fox are certainly not confined to southeastern Idaho or the Sun Ranch. Though wolves are well loved by tourists who see nobility in their pack loyalties, family bonds, and social interactions, they are hated by many westerners. Though predation by wolves has a small impact on livestock overall, ranchers who do experience livestock loss have a unique and personal exposure to wolves’ prowess at killing. That said, there is a big difference between an animal trying to take down its dinner, even if that meal is a cow, and a human trying to take down a perceived enemy, driving it to exhaustion and death. Judging from how the wolf gets treated by predator eradication programs, and how those programs are legislated by politicians, it’s clear that science isn’t driving wolf management.

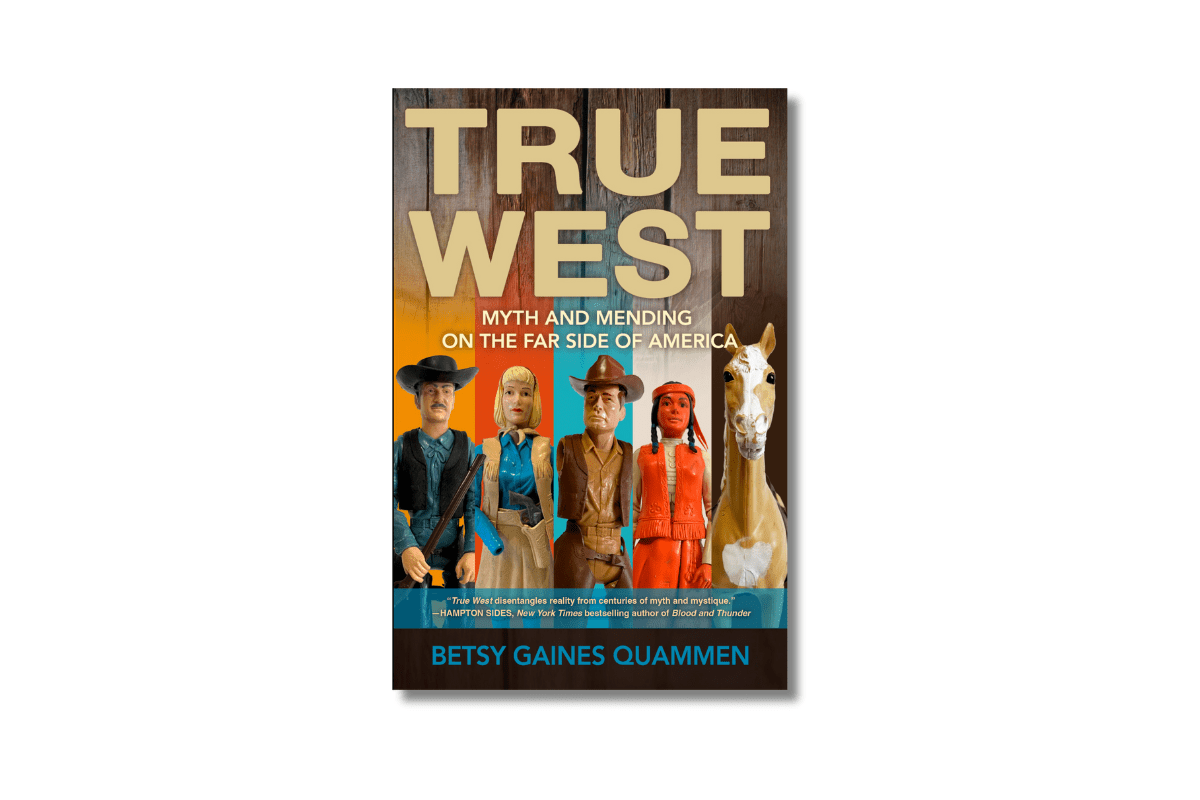

Betsy Gaines Quammen is a historian and writer who examines the intersections of extremism, public lands, wildlife, and western communities. She received a Ph.D. in history from Montana State University, a masters degree in environmental studies from the University of Montana, and a bachelor’s degree in English from Colorado College. She lives in Bozeman, Montana, with her spouse, writer David Quammen.

An assessment or critique of a service, product, or creative endeavor such as art, literature or a performance.

The Colorado Sun is an award-winning news outlet based in Denver that strives to cover all of Colorado so that our state — our community — can better understand itself. The Colorado Sun is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. EIN: 36-5082144

(720) 263-2338

Got a story tip? Drop us a note at tips@coloradosun.com