Uncategorized

A Hat Tip to 4 New Picture Books (Published 2022) – The New York Times

What to Read

Advertisement

Supported by

Picture Books

Alexandra Jacobs

THE UPSIDE DOWN HAT

By Stephen Barr

Illustrated by Gracey Zhang

COURAGE HATS

By Kate Hoefler

Illustrated by Jessixa Bagley

MAE MAKES A WAY

The True Story of Mae Reeves, Hat & History Maker

By Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich

Illustrated by Andrea Pippins

KAT HATS

By Daniel Pinkwater

Illustrated by Aaron Renier

Why did Stephen Sondheim, the greatest lyricist musical theater has ever known, use the word hat so much, from a song bleakly mulling whether anyone still wears them to “Finishing the Hat,” a mission statement for the soul in “Sunday in the Park With George”? No deeper meaning there, Sondheim insisted, after a critic noted the recurrence: “It’s the jaunty tone and the ease in rhyming that attract me,” he wrote in “Look, I Made a Hat,” his second volume of annotated verses.

Well, sure, hat rhymes with lots of satisfying words, including fat, flat, mat, splat, sat and cat, as Dr. Seuss, a great lover of hats who gave Bartholomew Cubbins 500 of them, made plain. The rhymability alone makes it good material for a picture book as well as a musical. But a hat can be deeply symbolic, too, as Sondheim well knew (in “Sunday,” it stands for nothing less than art itself). Jon Klassen showed this in his lauded Hat Trilogy, and so do a barbershop quartet of new books with wildly different tones.

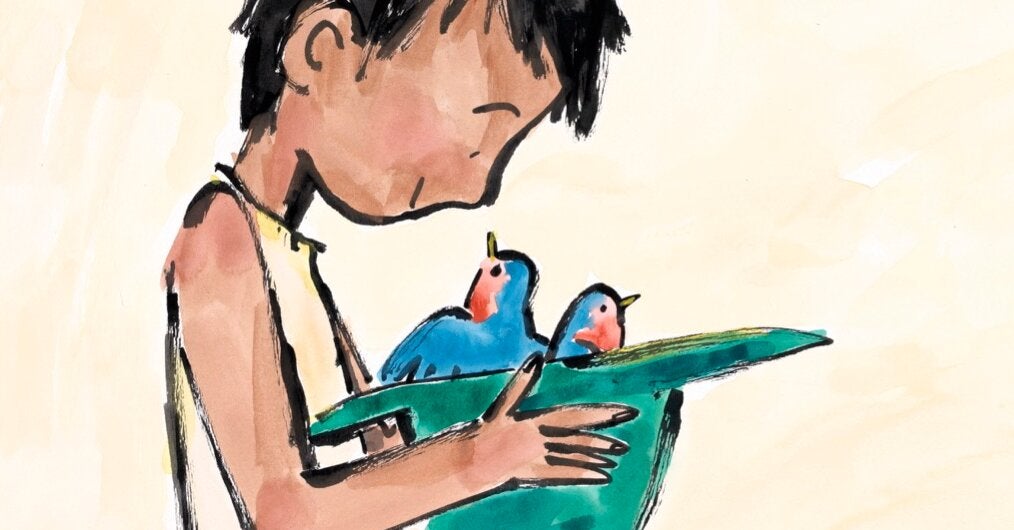

In “The Upside Down Hat,” a lullingly spare story by Stephen Barr with exquisite, Bemelmans-like illustrations by Gracey Zhang, a hat becomes a little boy’s entire support system. He is anonymous, though the names of his suddenly absent two best friends, Henry and Priscilla, and surroundings of palm trees and pillars suggest he once occupied a world of lush privilege. Waking up one morning, he discovers all his possessions, including bright orange stilts, are gone, except for this one crucial accessory.

What is a hat’s essential purpose? To protect the head, which this one does: from the sun beating down, and the rain. But in an instant it flips, like the famous optical illusion that shows a young or old woman depending on your perspective, and becomes a container: for drinking water, for cherries, for begged coins. After a long day of resourcefully facing his reduced circumstances, the boy goes to the top of a mountain, sleeps and dreams, falling into a kind of valley of the shadow where his lost things are restored to him, and yet are no longer what is really needed. When he wakes up, he’ll have new reason for optimism. With contrails of “The Little Prince” and magic-carpet colors, even adults will be transported.

“Courage Hats,” by Kate Hoefler, with illustrations by Jessixa Bagley, feels less universal but could be useful for children fearing travel or the unknown. Nervous about taking a train that goes through woods (“bear places”), a mysteriously unaccompanied minor named Mae decides to disguise herself as a bear by cutting up a paper bag and putting it on her head. Meanwhile a young bear, fearing a trip that goes through cities (“people places”), has done the same thing in reverse. They find each other, and solace, on the train, where they enjoy tea, snacks and views and gaze through a glass ceiling at the birds: “This feels like flying.”

It’s a head-scratcher, solved only on the last pages, why these two scaredy-bears are not in the actual air but on this sadly antiquated but cozy form of transport, which few but Alfred Hitchcock found ominous.

“Courage Hats” wants a little too forcefully to guide us into “deep” places where we will doff our hidey-hats to reveal our true selves — abstract concepts for the literalizing peewee set. When it comes to reassuring train bears, alas, it’s hard to top Paddington and his red sou’wester.

Another Mae, a character from real life, stars in “Mae Makes a Way,” by Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich, with illustrations by Andrea Pippins. Published to accompany a permanent exhibit at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, this is a biography of Mae Reeves, a renowned Philadelphia milliner who died at 104 in 2016 and received distressingly scant obituary coverage. Along with telling her story, “Mae Makes a Way” is also a pointed lesson about the limits of integration in cities where “Black women were often treated as though they were invisible,” as Rhuday-Perkovich writes at her best. “Hats were a way for these queens to be SEEN, shining a light on the dignity they always had.” There’s a special shout-out to the church ladies who kept Reeves’s business going long after fashion moved on.

Told in a largely linear, scrapbookish style and appended by interviews with Donna Limerick, the milliner’s daughter, and Reneé S. Anderson, the head of collections at the NMAAHC (where Reeves’s shop has been painstakingly recreated), “Mae Makes a Way” is a fine introduction to a determined trailblazer. It’s mostly facts, with occasional forays into modern lingo (“live their best lives,” “build better tomorrows”) and fillips of poetry (“glimmery hats, shimmery hats, snappy hats and happy hats”). The tantalizing close-ups of tulle, feathers and other furbelows cry out for an edition with paper dolls.

By contrast, creating an aesthetic that’s vaguely familiar yet thoroughly out of time, “Kat Hats,” by Daniel Pinkwater, with illustrations by Aaron Renier, plunges us into a geography of the absurd. The hats that Matt Katz sells in his shop in snowy Pretzelburg are not decorative and uplifting but warming. In fact, they are not hats at all. They are cats.

Never mind that, with rare exception, you can’t train a cat to do anything. “Kat Hats” sends up the familiar directive to wear a hat because “90 percent of body heat is lost through the top of the head,” proposing that if properly topped, one “could even visit the North Pole in summer pajamas and remain comfortable.”

When the good-witch mommy of Katz’s friend Old Thirdbeard vanishes up a mountain without her pointy hat, sucking on a blueberry and avocado ice pop (hats and mountains are perennial pairings in children’s literature), she is stricken with brain freeze, a.k.a. “frozen think-muscle.” It falls to Thermal Herman 6⅞ths, the showboat of Katz’s inventory, to fashion himself into a fedora, hitch a ride on a moose’s antlers that double as a hatrack and save her. With jolly maximalism and Shrinky Dinks shadings, this is a book that invites children to take off their thinking caps, relax and revel in pure silliness.

Alexandra Jacobs is a Times book critic and the author of “Still Here: The Madcap, Nervy, Singular Life of Elaine Stritch.”

THE UPSIDE DOWN HAT

By Stephen Barr

Illustrated by Gracey Zhang

48 pp. Chronicle. $17.99.

(Ages 5 to 8)

COURAGE HATS

By Kate Hoefler

Illustrated by Jessixa Bagley

48 pp. Chronicle. $17.99.

(Ages 5 to 8)

MAE MAKES A WAY

The True Story of Mae Reeves, Hat & History Maker

By Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich

Illustrated by Andrea Pippins

48 pp. Crown. $18.99.

(Ages 7 to 10)

KAT HATS

By Daniel Pinkwater

Illustrated by Aaron Renier

40 pp. Abrams. $17.99.

(Ages 4 to 8)

Follow New York Times Books on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, sign up for our newsletter or our literary calendar. And listen to us on the Book Review podcast.

Apple's Influence on China: Patrick McGee makes devastatingly clear in “Apple in China” that the company’s decision to manufacture about 90 percent of its products in China has created an existential vulnerability not just for Apple, but for the U.S.

Boomer Radicals in Vermont: Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel, “Spent,” is a domestic comedy about ethical consumption under capitalism.

Winner of the International Booker Prize: “Heart Lamp" is a collection of stories about Indian Muslim women’s daily struggles with bothersome husbands, mothers and religious leaders.

A Manga Megastar Terrifying Work: The horror cartoonist Junji Ito, creator of popular series like “Tomie” and “Uzumaki,” is one of manga’s biggest stars in the U.S. Here's a look at how he carefully nurtures his readers' discomfort.

The Book Review Podcast: Each week, top authors and critics talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here.

Advertisement