Uncategorized

Big problems – Craig Medred

Enter your email address to follow Craigmedred.news and receive notifications of new stories by email.

{{#message}}{{{message}}}{{/message}}{{^message}}Your submission failed. The server responded with {{status_text}} (code {{status_code}}). Please contact the developer of this form processor to improve this message. Learn More{{/message}}

{{#message}}{{{message}}}{{/message}}{{^message}}It appears your submission was successful. Even though the server responded OK, it is possible the submission was not processed. Please contact the developer of this form processor to improve this message. Learn More{{/message}}

Submitting…

Take it from Ann Bryant, executive director of the Tahoe, Calif., Bear League, bears don’t kill people because “we’ve never had a bear kill anybody.”

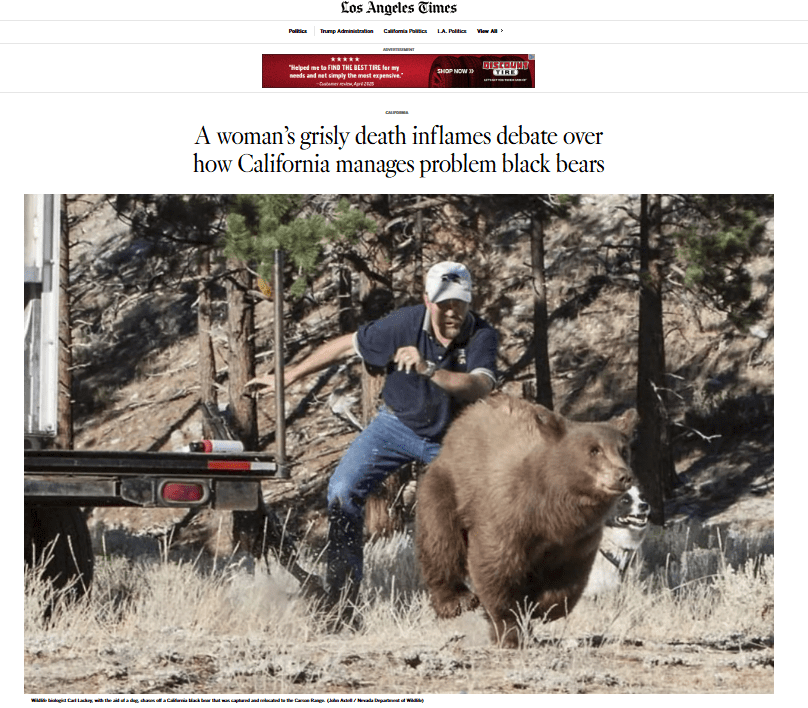

This is what she told the Los Angeles Times in the wake of the death of 71-year-old Patrice Miller, whose partially eaten remains were found in her Downieville home surrounded by the footprints of a bear.

Sierra County authorities last year reported that an autopsy had confirmed Miller was killed by a black bear in 2023, and CBS News at the time reported this as “the first-ever recorded case of such a deadly attack.”

“California confirms first fatal black bear attack on human” was the rather flawed headline on the CBS story, given that fatal black bear attacks, though extremely rare, have long been known to happen in the U.S.

Wikipedia’s name-by-name list of people killed by black bears goes back to Carl Herrick, a 37-year-old hunter, apparently killed by a black bear in Vermont in 1943, and 3-year-old Carol Ann Pomeranky, “who was taken by a bear outside of her home on the Marquette National Forest in Michigan. She was dragged 100 yards. The bear was tracked and killed.”

Canadian bear researcher Stephen Herrero and colleagues tracked deadly black bear attacks in North America back even further to the start of the 20th Century. In a peer-reviewed study published in the Journal of Wildlife Management in 2011, they added that most of these “fatal black bear attacks were predatory.

“Once predatory behavior is initiated, it may persist for hours unless it is deterred. After one person has been killed by a black bear, the bear may attempt or succeed in killing other nearby people, as demonstrated by the three incidents in which two or three people were killed.

“Such bears appear to be strongly motivated, as if a switch had been thrown. Once a black beear has killed a person there is an increased chance that it will try to kill other people. Such

bears should be removed from the wild.”

The Herrero paper, published in the Journal of Wildlife Management, outlines why the Alaska Department of Fish and Game developed a policy of hunting down and killing predatory bears, if possible, and executing bears that habituate to humans and lose their fear of people.

In the wake of Miller’s death, California is still debating how it should manage a black bear population that now numbers an estimated 60,000.

To put this in perspective, California – a state about a quarter the size of Alaska – is now home to about about about 60 percent of the estimated 100,000 black bears in Alaska. Or put another way, California now has about twice as many black bears per square mile as Alaska.

California also happens to be home to more than 50 times the human population of Alaska. Thankfully, most of those people stay in heavily urbanized areas that bears avoid. That’s a good thing that many in California never venture into bear country.

It’s a bad thing in that the bears displaced from the urban areas further increase the population of bears per square mile in the remaining rural areas of a state that has developed a very large and healthy black bear population since killing off the last of its grizzly bears in 1924.

That happened only 13 years after the “bear flag” adorned with a grizzly bear was officially adopted by the “California Republic.”Updated in 1952 to feature a more grizzly-like grizzly, the flag remains with the bear as its main element today, according to California State Parks, which adds that “the Legislature passed a separate bill making the grizzly the State Animal in 1953.”

California’s grizzlies were long extinct by then and efforts to bring them back that began decades later have gone nowhere, although the California State Senate last year unanimously voted to declare “2024 the ‘Year of the California Grizzly Bear’ to mark the 100th anniversary of the extirpation of California’s official state animal,” according to the California Grizzly Alliance, which is pushing for the reintroduction of grizzlies.

A 2019 poll found 63 percent of Californians “at least somewhat supportive of reintroduction” and scientists have concluded the state still has wild areas that could support a population of grizzlies.

But no California lawmaker has shown the nerve to sponsor legislation ordering restoration of the biggest of the North American bears. A bigger and more volatile cousin of the black bear, the grizzly still generate some fear among a segment of Californians.

Black bears are a different matter.

As the Bear League’s executive director told the Times, Miller “would roll in her grave if she knew that in her death people would create a situation where people were going to mistreat bears, because she loved bears.”

Or at least the parts of her not devoured by the bear would roll in her grave. She was reported to have lost much of her right leg and left arm to the bear before her body was found.

Some have also suggested Miller was part of the bear problem in Downieville. Sierra County Sheriff Mike Fisher told the Times that some of her neighbors complained that she had allowed bears to regularly get into her garbage, which is food for bears, and that the animals were feeding on tasty morsels she tossed onto her deck for her cats.

Miller’s daughter, according to the Times, “told sheriff’s officials that bears were ‘constantly trying’ to get into her house, and that ‘her mother had physically hit one’ to keep it out. One particular bear, which Miller had nicknamed ‘Big Bastard,’ was a frequent pest.”

Bears that behave like Big Bastard in or around Anchorage, or almost anywhere in Alaska for that matter, would inevitably be executed. A record 41 of them – 14 brown/grizzly bears and 27 black bears – died in the Anchorage area in 2018.

Alaska can get away with killing problem grizzlies because, unlike in other states, the grizzly population in the 49th state is healthy rather than exterminated, endangered or threatened.

Some of those 41 dead bears were shot by homeowners defending themselves or their animals, but a significant number were gunned down by agents of the state underlining their regularly preached warning that “a fed bear is a dead bear.”

This is the Alaska mantra because Alaskans have come to recognize that fed bears become dangerous bears, and that humans need to kill the dangerous bears so they can live safely with the bears that understand it is a good idea to avoid people.

The well-known warning “that a fed bear is a dead bear’‘ also helps to keep most of the wildlife lovers with a tendency for loving wildlife to death from intentionally feeding bears, a temptation for some.

Acording to a paper published in the journal of the Society for Conservation Policy in 2023, feeding wildlife today “represent(s) one of the most popular forms of human–wildlife contact in modern times.”

This has not always been the case, the Ireland-based authors of the paper added, citing a “relationship (that) is highly dynamic, ranging from periods of tolerance to conflict. Specifically, humans have historically alternated between phases of appreciation, reverence, utilization, acceptance, and retaliation, with this variation in our regard for wildlife driving how we interact with them.”

In these times, there is in the U.S. something of an urban-rural divide in regards to wildlife interactions with residents of urban areas more inclined to attempt to befriend wildlife while rural residents still lean toward killing them, if they become a nuisance, or killing them and eating them, if they happen to be tasty.

This might help to explain the problematic differences between managing bears in heavily urbanized Californa, where many are offended by the idea of killing bears in the name of safety, and Alaska, where doing so is accepted as the consequence and cost of living in an area with healthy bear populations while recognizing that the bears are not our friends.

Near the end of the 20th Century, a Californian named Timothy Treadwell brought the California view north in the belief he and the bears could be friend. That didn’t work out so well. He ended up getting himself and his girlfriend killed and eaten by a bear in Katmai National Park and Preserve in 2003.

Any number of Alaskans, including one former candidate for the U.S. Senate from Alaska, are alive because they took a view far different from that of Treadwell. The Senate candidate actually ended up running for office in the 49th state with the claim that “he killed a grizzly bear in self-defense after it snuck up on him.”

A California candidate for Congress making such a “manly” claim would be villified even if the candidate were a woman.

None of which is meant to suggest that Alaskans have any desire to eliminate bears the way Californians did. Alaskans are pretty tolerant of bears right up until the point the bears attack or begin to lose their fear of humans – the point at which bears truly become dangerous.

Human-habituated black bears have over the years become a continuing problem in many states as American attitudes toward bears have become increasingly urban. A 74-year-old Colorado man was seriously injured last fall when a black bear sow with three cubs in tow ventured into his Hinsdale County home.

“Clearly, these bears were highly habituated and were willing to enter an occupied house with the residents sitting just feet away,” a representative of Colorado Parks and Wildlife later told USA Today. “When a bear reaches this level of human habituation, clearly a lot of interaction with people has already happened.”

Alaska is, admittedly, not immune to the habituation problem. The late Charlie Vandergaw, an Anchorage resident, for years ran a sizable, personal bear habituation operation in a remote area north of the city accessible only by small plane.

Vandergaw loved his bears, but his love of bear wasn’t the misguided friendship of Treadwell. He was fostering a relationship more akin to that between people and dogs.

Vangergaw was of the view bears could be trained to behave safely around people, and they largely did when he kept them well fed and made clear the rules that governed the continuation of the handouts.

Training bears was a big ego trip for Vandergaw, but he well understood the risks. He recognized there were bears that were dangerous, would always remain dangerous and for that reason had to be avoided or killed, because even if you’ve never witnessed “a bear kill anybody,” bears, even black bears, can and do kill people.

Eight years ago, a black bear killed 16-year-old Patrick “Jack” Cooper on Bird Ridge just east of Anchorage along the Sterling Highway. He was not the first to die or be seriously injured in a bear attack in and around Alaska’s largest city and is unlikely to be the last despite the efforts of state and city officials to manage the Alaska bear population in the name of public safety.

California might want to take a note. But then again, California is, well, California.

Categories: News, Outdoors

Tagged as: a fed bear is a dead bear, alaska, bear attack, bear attacks, bear management, California, Colorado, dead woman, downieville, Herrero, Lake Tahoe, Los Angeles Times, problem bears, Vandergaw

craigmedred.news is committed to Alaska-related news, commentary and entertainment. it is dedicated to the idea that if everyone is thinking alike, someone is not thinking. you can contact the editor directly at craigmedred@gmail.com. View all posts by craigmedred

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

{{#message}}{{{message}}}{{/message}}{{^message}}Your submission failed. The server responded with {{status_text}} (code {{status_code}}). Please contact the developer of this form processor to improve this message. Learn More{{/message}}

{{#message}}{{{message}}}{{/message}}{{^message}}It appears your submission was successful. Even though the server responded OK, it is possible the submission was not processed. Please contact the developer of this form processor to improve this message. Learn More{{/message}}

Submitting…

Continue reading