Uncategorized

The 'bison skull mountain' photo that reveals the US's dark history – BBC

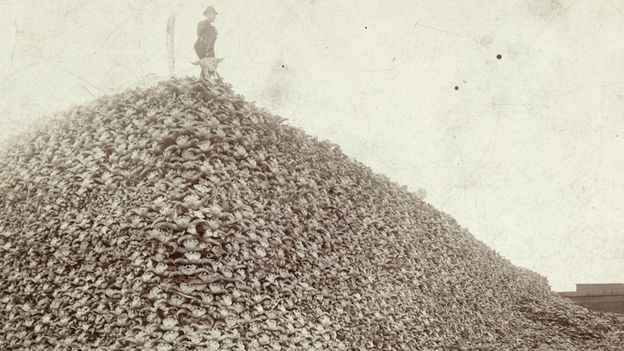

The photo of two men standing on a mountain of bison skulls is well known as a symbol of hunting during the colonisation of the US. But there's a more sinister story behind it – with a surprising modern message.

Two men in black suits and bowler hats pose with a gravity-defying mound of bison skulls. The 19th-Century image is disturbing – thousands upon thousands of skulls piled in neat rows, towering towards the sky. But beneath the macabre first impression, the photo holds a darker secret still. These skulls aren't just the product of overzealous hunting in the US – and those men aren't hunters, either.

The skulls, experts say, are the evidence of an organised, carefully calculated campaign to eradicate the bison, deprive Native Americans of a vital resource, and drive the few communities that survived onto small reservations where they could be controlled by the newly arrived white settlers.

"This image is an example of colonial celebration of destruction," says Tasha Hubbard, a Cree filmmaker who is an associate professor at the Faculty of Native Studies at the University of Alberta in Canada. Hubbard describes the extermination of the bison as a "strategic" part of colonial expansion. The eradication of the animal "was seen as the taming of the West, of domesticating this wild space that was needed in order for expansion of settlement".

The colonial mass slaughter of bison dealt a lasting blow to tribes that relied on the animal for sustenance. In the aftermath, nations reliant on bison fared measurably, permanently worse than nations that were never bison-reliant, for example suffering from higher child mortality than those other nations, according to a comparative study. The study concludes that the loss set the bison nations on a fundamentally different trajectory that continues to this day.

Native Americans had hunted bison for centuries. For bison nations, it was part of their primarily nomadic culture and the animals provided them with vital sustenance – meat for food, hides for shelter and clothing, and bones for tools. (In common parlance and historical sources, the animals are often referred to as buffalo, as that's what early settlers called them – though the two are in fact different.)

Indigenous peoples across North America relied on the animal, Hubbard says. "So to remove that keystone species was to weaponise starvation against indigenous peoples: to weaken us in order to control us and remove us from our territories."

Despite the bisons' usefulness, estimates put the Native American hunters' take at less than 100,000 a year, hardly making a dent on the early 1800s population of between 30 and 60 million bison.

By 1 January 1889, there were just 456 pure-breed bison left in the US – and 256 of them were in captivity, protected in Yellowstone National Park and a handful of other sanctuaries.

The reasons for the mass bison slaughter are numerous: they include the building of three railway lines through the most populous bison areas, which brought new demand for the animal's hide and meat; modern rifles that made killing bison relatively easy; a lack of protective measures which could have curbed hunting. But there was also more sinister, targeted reason for the animals' decline than just an increased demand for bison products – more on this later. And even the settlers' seemingly practical need for bison meat and hide was ultimately intertwined with colonisation and conquest, historians say.

"A desire for wealth and power in the form of land ownership, chattel slavery, the drive for unending growth and profit, and the commodification of natural resources is the reason for the intense overhunting of bison and the political and physical attacks on indigenous nationhood and humanity over five centuries," says Bethany Hughes, a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, and assistant professor at the University of Michigan's department of Native American studies.

When the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, it accelerated the decimation of the species. In 1871, a Pennsylvania tannery developed a method of converting bison hides into commercial leather. Swarms of hide hunters decimated central plains herds with a "shocking rapidity", one study noted.

The infamous image of bison skulls was taken at the Michigan Carbon Works, a refinery that processed bones. There, the bison bones were processed into charcoal that the sugar industry used to filter and purify sugar – the bones were also used as glue and fertiliser.

"This photo records a remarkably successful business that was built on the waste created by American Western expansion and its accompanying racial logics of Native American inferiority," says Hughes.

"Colonialism and capitalism travel together," Hughes adds. "To benefit from and encourage the kind of economic success this company had processing bison bones, [which] were the byproduct of the sometimes-violent tactics of American settler colonial expansion, was to benefit from – and participate in – colonial projects that stripped Indigenous peoples of land, nationhood, and culture.

"This photo is not a bracing reminder of the harms of colonial pasts. It is an indictment on commercial consumption practices that obscure the material and ethical conditions that make luxuries like refined sugar readily available and seemingly benign."

Killing bison was also part of military campaigns that used resource deprivation as a tactical move.

It has been well documented that Western army officials sent soldiers to kill bison as a way of depleting Native American resources during the colonisation of the US. An analysis by historian Robert Wooster in his book The Military and United States Indian Policy acknowledges that General Phillip Sheridan, an army officer responsible for the "Total War" strategy against Southern Plains tribes,"recognised that eliminating the buffalo might be the best way to force Indians to change their nomadic habits".

Sheridan was recorded telling legislators who were trying to pass laws to protect the dwindling herds: "[Hunters] are destroying the Indians' commissary. And it is a well known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage…for a lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated."

Sheridan wrote in a letter to a fellow general in 1868: "The best way for the government is to now make [the tribes] poor by the destruction of their stock, and then settle them on the lands allotted to them."

Another army official – Lieutenant Colonel Dodge – told a hunter: "Kill every buffalo you can! Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone."

The Native American tribes knew what was happening. Satanta, chief of the Kiowas tribe, in the Great Plains,recognised that "to destroy the buffalo meant the destruction of the Indian" – as Billy Dixon, a bison hunter and frontiersman from Texas, recalled in his autobiography. "General Phil. Sheridan, to subdue and conquer the Plains tribes for all time, urged and practiced the very thing that Satanta was fearful might happen," Dixon added.

Depriving the Native Americans of their bison meant they were forced to move onto the new reservations the Western army had established for them, in order to grow food to survive.

The army's tactics worked. The Kiowa Tribe members were later driven onto a reservation in Oklahoma. Within one generation, the average height of Native Americans who had relied heavily on bison and so were most impacted by the slaughter dropped by more than an inch (2.5cm). By the early 20th Century, child mortality was 16% higher, and the income per capita among bison nations has remains 25% lower compared to nations that weren't so reliant on bison.

However there has been some debate over the years over the kill-off. How could hunters kill 30 to 60 million animals? That was the question posed by a 2018 study which offered a disease epidemic as the answer. Two diseases in the country at the time – anthrax in Nebraska and Texas tick fever in Montana – would have been "sufficiently deadly to wipe out tens of millions of animals", the study notes.

More like this:

• How a tribe brought back its sacred California condors

• Why grazing bison could be good for the planet

• The largest dam removal in US history is complete

Regardless of the cause, the bison populations never fully recovered and the species is still listed as near-threatened. But in recent years efforts have been made to bring bison back to the Great Plains (they are incredibly important to the prairies ecosystem). In the US government's 2023 Inflation Reduction Act, $25m (£19.7m) was pledged to restore bison across the US.

Smaller efforts are already underway: 1,000 bison raised on reserves belonging to environmental non-profit The Nature Conservancy have been returned to their ancestral grazing lands. A restoration project in Montana aims to bring 5,000 bison back to the prairies and tribes have returned 250 bison to their land in a partnership with the National Wildlife Federation.

The message behind the striking mount of bison skulls image has been lost over time, adds Hughes, who says the image carries a simplistic message that allows viewers to feel sadness about the past, but does not force them to confront "the ways that colonial and capitalist systems continue to negatively shape our environment and our lives".

"More than that, this photo points to the ways that consumers of products are the engine that drives the colonial machine.

"If you dehumanise another person or objectify a living being as a 'natural resource' you have revealed your own lack of humanity and a misunderstanding of what it means to live in relationship with the world around you," Hughes says. "This is an important message to share with the public because this is an ongoing problem, not a historical one."

—

For essential climate news and hopeful developments to your inbox, sign up to the Future Earth newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.

For more science, technology, environment and health stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook and X and Instagram.

A woman who allegedly was the head of the Catholic Church became one of the most controversial Middle Ages tales.

Hiding in an attic, Jewish man Curt Bloch found inspiration through crafting anti-Nazi parody.

Watch how the maps and images of our planet from above have changed over the last two millennia.

From a shipwrecking yard in Bangladesh to a river of iron dioxide in Canada, a deep dive in Ed Burtynsky's work.

It starts nearly 40 years ago, when a teenage girl is pulled out of obscurity and thrust into the spotlight.

How America's first professional female tattooist broke through into an art form historically dominated by men.

Valentine’s Day is thought to celebrate romance but rude cards soured the holiday for its recipients.

Why a famous photograph of King Richard III's skeleton was a happy 'accident'.

An unexpected WW2 experiment by behaviourist B F Skinner proved that pigeons could be used for missile guidance.

In Sri Lanka, a charming elephant cheekily halts traffic for treats.

Watch two rhinoceroses involved in a game of 'kiss and chase'.

While her three offspring take a leisurely bath, this Bengal tiger mother must find food for the entire family.

Watch red foxes challenge the Steller's sea eagle, the world's heaviest raptor, as they search for food in Japan.

How a dwindling group of veterans from the American War of Independence were featured in early photographic form.

Watch as David Attenborough reveals the unique behaviour of a mother seal to protect her pup in icy waters.

Watch the world's largest species of goat fight for the right to mate, teetering on the edge of perilous drops.

The Tam Nam Lod Cave is home to over a quarter of a million swifts. But there are hidden dangers.

In 1948 a famous artist and an innovative portrait photographer attempted to create something unbelievable.

The actor recalls being at the Mandela film premiere when he heard the anti-apartheid politician had died.

The mudskipper is a fish that can leap with a flick of its tail. Watch a particularly agile specimen in action.

BBC Special Correspondent Katty Kay and best-selling author Gretchen Rubin discuss her new book, Secrets of Adulthood, and why one-sentence bits of advice can be so impactful.

Former staff and guests have come forward with their memories after an appeal to track down the faces featured in an exhibition.

The opposite of an escapist blockbuster, the eighth and apparently final outing for Tom Cruise's Ethan Hunt is the doomiest and gloomiest yet in the action-adventure franchise.

Big skies, bold cities and iconic prison islands: these destinations offer a familiar feel with a global twist.

Gérard Depardieu was found guilty of sexually assaulting two women on a film set. It's a verdict which could have a big impact on the country's film industry.

Copyright 2025 BBC. All rights reserved. The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites. Read about our approach to external linking.